The Cretan insurrection of 1866 is primarily remembered today for the self sacrifice of the Christian Cretans rebels at the Monastery of Arkadi who, in March of that year, rather than surrender to the Ottoman troops storming the building, killed themselves and their dependents by exploding the gunpowder magazine; the fighting and the resulting explosion killing over 550 of the defenders as well as 450 Ottoman troops. However the events which followed and which were played out in Selino Kastelli, as Paleochora was then called, though lesser known, had as much significance in the political history of Crete.

Upon the outbreak of the rebellion the Ottoman authorities had declared an embargo on all foreign shipping coming to Crete; ships stopping at the island could only do so at five designated ports, all on the north coast. This was in part to try to prevent Greeks and others who sympathised with the Cretan cause from landing arms and men to assist the rebels and in part to prevent an exodus of Christian Cretans to Greece; while they remained on the island they were a drain on the resources of the rebels. After the Arkadi explosion the remaining Christian fighters and their dependents withdrew to the west, to the Selino, Omalos and Sphakia districts, but with the onset of winter, the plight of the women and children with them grew desperate. As Ottoman troops increased their pressure on the insurgents, burning the few remaining crops and destroying their villages, many of the non-combatants moved to the coast in an attempt to find shipping to take them off Crete and to safety.

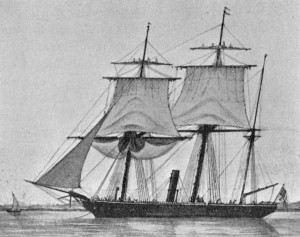

From the very start of the insurrection the British Government had been less than sympathetic to the Cretan cause; British commercial and political interests at that time dictated that Crete remain part of the Ottoman Empire and in any case, with rebellions against British rule taking place in Ireland and India, Britain could not be seen to be supporting independence movements. Accordingly, the British Consul in Chania, Charles Dickson, was repeatedly instructed to maintain strict neutrality in what was seen as an internal Ottoman problem. At Dickson’s request, and in order to safeguard British citizens and British property, the Royal Navy stationed a gunboat in Chania and in December 1866 this duty fell to HMS Assurance, captained by Commander William Pym. Between Dickson and Pym there developed the belief that, in spite of their specific orders, something had to be done to aid the Christian refugees on the south coast.

On 8th December 1866 Dickson asked Pym to:

…cruize close to the western coast of the island …[and]… seize every available opportunity for affording refuge to any Christian in distress who may seek protection on board your ship, and….convey the same to any port in Greece that you may deem advisable.

On arrival off Selino-Kastelli on the afternoon of 10th December 1866 Pym discovered:

“…25 wounded and sick men, 126 women, and 164 children (Christians) [who] sought refuge on board from the district of Selino; and as they were exposed to hunger and the inclemency of the weather (the mountains being covered with snow), their villages having been destroyed and as they expected no quarter from the Turks […..]I considered it my duty to receive them on board, and having being requested to take them to Piraeus, I did so accordingly…”

The reaction to Pym’s voyage in Britain was mixed; the public, the press and certain politicians were all in favour of it but the Government most certainly were not. Pym was, rather reluctantly, praised by the Navy for his humanitarian efforts but shortly afterwards relieved of his command of HMS Assurance and returned to England. He never again receiving a seagoing post and retired from the Navy in 1873 under rather dubious circumstances. Dickinson, the Consul, was given strong advice not to get involved in any further such activity and left the island early in 1868, dying in Constantinople in 1869.

Their humanitarian action, a clear breach of the Ottoman embargo and of International Law as it stood in those pre-Geneva Convention days, produced the effect that the British and Ottoman Governments most feared; within days war ships from other major powers, French, Russian, Austrian, Italian and Prussian, began visiting the south west coast and evacuating refugees from Selino (Paleochora), Tripiti Bay, Sougia, and Agia Roumelli. (The American consul in Chania, who after all the other participants were dead and thus could not respond, claimed that he had been the instigator of the voyage of HMS Assurance and promised American ships would also participate, but none appeared.) The political crisis brought on by the Cretan insurrection grew ever more complicated with the involvement of the outside powers and the rebels more intractable knowing that there was a means of safe passage for their dependents.

In the end, the only major European power that did not take part in the evacuation exercise was Britain; the visit of HMS Assurance to Paleochora being the only British government involvement saving the refugees, though the British public did raise considerable amounts of money for their relief, raising £850,000 in 2010 terms from a donor pool of less than 300 people, with the Greek ex-patriot community doing the most.

The insurrection eventually came to an end in 1869 after the Ottoman Empire threatened to declare war on Greece for its continued support of the rebels, support chiefly expressed by the means of arms ammunition and men being brought to the island by blockade running ships such as the ‘Arkadi’. The European powers made it clear the Greece that she could expect no support in the event of such a war; ultimately Greece succumbed to the pressure and on 18th February 1869 at a Conference of the Great Powers in Paris, diplomatic relations between Greece and Turkey were restored and, Greece having withdrawn support from the insurrectionists, relative peace returned to the island.

Recent Comments